Welcome back to today’s episode of Marvelous Videos, where we’ll go through this incredible film in depth. Hayao Miyazaki directed the film. This hotshot was released in 1997 and immediately won the Best Picture award at the Japanese Oscars that year. After all, why not?

The picture is as theoretically rich as it is sophisticated, engrossing the audience with deeply interwoven substance. It may appear at first to be a film about the ongoing struggle between man and beast, as well as the countless lesser battles that take place. However, it appears to scratch beneath the surface, leading viewers to experience deeper emotions.

The video recounts a beautiful story of love, hate, humanity, and conflict with mesmerizingly produced animation based on 80,000 hand-drawn cells and a captivating soundtrack. What more could we ask for from a movie? Let’s take a closer look at this incredible piece of work, including the plot, characters, and hidden meanings that director Miyazaki urged his audience to consider. Let’s get this party started, shall we?

The story begins in a world where forests have blanketed the landscape since the beginning of time. Not only did animals live in these forests, but so did humans, forest spirits, and animal gods.

In the past, man, beast, and higher entities coexisted in peace and harmony, assisting one another and living a simple existence. The forest gods had pledged their loyalty to the forest spirit, a being who embodied the essence of all woods and life itself. However, when man gained knowledge of technology and resources, he began to devastate the very trees that provided for him.

The forest gods, who had vowed to safeguard the forest, their home, from man’s anger or die trying, were not pleased. However, the order is disrupted by new developments in the form of the emergence of terrible demons bent on ravaging life.

A worried young boy is shown riding a red elk, a hybrid of antelope, horse, and mountain goat. The boy’s name is Ashitaka, and he is an Emishi prince from Japan’s Muromachi period, which spanned the 14th through 16th centuries.

As the hamlet’s wise woman has asked, Ashitaka is on a mission to gather everyone back to the village. Soon after, he catches up with his sister and her companions, who informs him that something is wrong in the forest: “the birds have all gone, and the animals as well.”

To find out what’s going on, Ashitaka travels to the village’s watchtower to meet Ji San. He gallops through the verdant pastures on his quick elk, heading for the wooden watchtower. Ji San assures him that whatever lurked in the bushes was not human. Soon, the disturbances in nature became more pronounced, and there it was, a beast of tremendous monstrosity, a demon in the flesh.

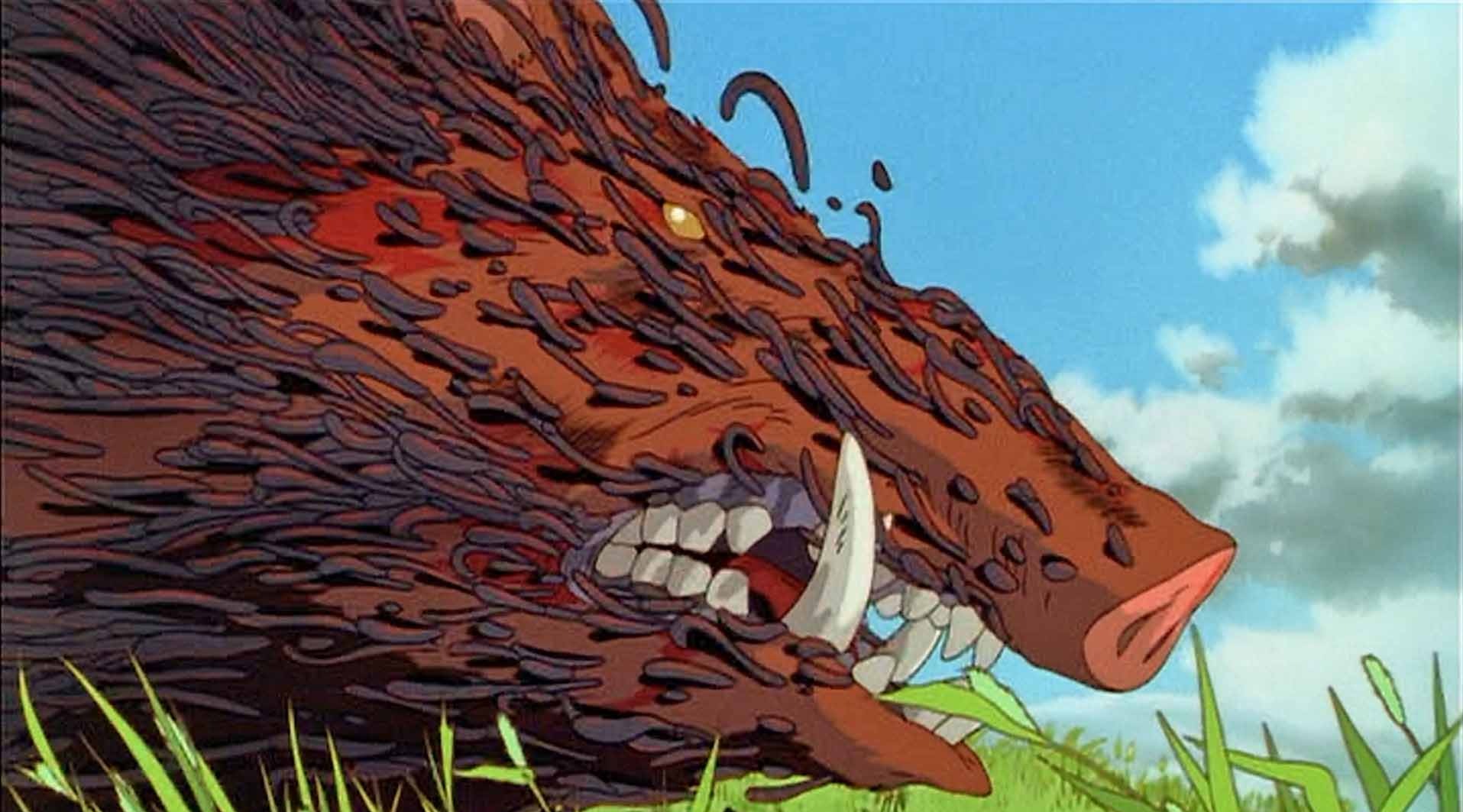

The demon broke through the stoned wall and hastily approached the watchtower, where Ashitaka’s elk Yaku was standing. This demon called the “TatariGami”, had skin and flesh that seemed to be composed of thousands of worms. We find out that it could also shapeshift as its legs increase in number, from four to eight. Its glowing red eyes were fixated on its target. Just as the giant bug-shaped worm fleshed TatariGami entered sunlight, it showed its true form, a giant boar.

We realize that the demon used to be the Forest god of boars. Changing its form once again to take the form of a spider, it resumed its march towards Yaku. The elk stood there spellbound and unable to move at the sight of the grotesque beast while Ashitaka somehow managed to urge the elk into making a run for its life. Alas! the demon destroyed the watchtower.

As the demon made its way towards the village, Ashitaka summoned his ride and chased the beast. Ji San had warned Ashitaka that the demon was cursed and that he shouldn’t let it touch him. Ashitaka’s bravery and courage in charging the TatariGami, putting his own life in grave danger were indeed admirable. Ashitaka attempts to draw the demon away from the village, trying to reason with and request the beast as though a beast could be reasoned with! Adding insult to injury, the demon eyed Ashitaka’s sister Kaya and two of her friends.

The young prince had had enough at this point and he shot an arrow straight into the demon’s glowing eye and aimed another towards his skull. However, the demon managed to get a grip on Ashitaka’s right arm with one of its wormy extensions. The TatariGami faded away, revealing the true form of the Boar God before dying. Simultaneously, Ashitaka’s right arm was afflicted by an evil mystical wound. The wise woman of the village approaches the fallen demonic god, promising to bury him and paid her respects.

The dying boar wasn’t done just yet as even on its death bed it had managed to curse the village, wishing upon them the same suffering that he had gone through (“Soon, all of you will feel my hate, and suffer as I have suffered!”). After expelling his last bout of intense hatred and rage, its skin and flesh melted away, filling the vicinity with a pungent smell. Blood oozed from its body and soon only its skeleton remained.

Later, the wise woman concludes that the Boar God had become a demon because it was filled with rage and feared his own death. After all, an iron ball had penetrated his body and corrupted the boar. In this vulnerable state, he had transformed into a ruthless demon with no qualms about violence. The portion of Ashitaka’s hand that the demon touched was cursed and would soon spread through his body, making him suffer and eventually leading to his death. The wise woman tells Ashitaka that since the boar had come from the West, the only way to learn the means to lift his curse was to travel to the West.

However, she warns him that there was evil brewing in that direction. Whatever may be the outcome of Ashitaka’s perilous journey, his run with his tribe was over as per the Emishi laws. He would now have to abandon his village forever and live alone. The Emishi were a tribe who were persecuted by an emperor five hundred years prior to this day’s events. Since then, they had lived in the East, as each successive generation of the Emishi continued to grow weaker. Their ray of hope, the strong and courageous leader that was Ashitaka, was now being taken away by fate. Ashitaka proceeds to cut his hair as ritual dictated and left the village in the thick of the night.

“It is time,” says the woman, “for our last prince to cut his hair and leave us.”

If you are wondering why Ashitaka cut his hair before leaving his village, the reasons are manifold. Firstly, his hairstyle was unique to his tribe, and he didn’t want anyone to discover his identity. Secondly, being banished from his village by the wise woman, he couldn’t carry the Emishi legacy anymore. Certain fan theories also suggested that since it was almost certain that the curse of the TatariGami would bring him death, he should have simply amputated his arm, but they’re never is such a simple answer to the mystical and this theory had no logical basis.

Coming back, the movie shows Ashitaka’s travel through the woods, crossing rivers, and climbing up and down many hills to discover a way out. In his heart, he carries a hope to cure his land and the home to gods and spirits. These scenes truly bring out the beauty and the hard work behind the 80,000 hand-drawn cels used by Studio Ghibli instead of relying on CGI. A big shoutout to the immensely talented Artist Kazuo Oga for these time-consuming and compelling landscapes.

Ashitaka finally reaches his destination from where he could see a group of samurai warriors massacre a village. These cold-blooded killers spared no one, including women and the elderly. Ashitaka is soon spotted and dubbed a warrior. He gives Yaku a jolt and gets moving but notices a samurai slashing a woman and shooting an arrow. However, something takes over Ashitaka’s arm, and the arrow amputates both arms of the samurai and pins them on a tree.

Ashitaka warns the other two samurais who were chasing him on horses, but they paid him no heed and one of them is beheaded. Ashitaka notices that his mark had gotten bigger. The young prince’s curse was both his bane and boon. It gave him supernatural powers and abilities, but whenever used, the curse spread further through his body. Ashitaka managed to escape the savage samurais and disappeared deep into the woods.

Later, he visited a town’s local market and attempted to purchase rice in exchange for a lump of pure gold. The shopkeeper didn’t recognize the gold which escalated into chaos, attracting everyone’s attention, including a monk who was inadvertently saved by Ashitaka earlier in the massacre. The Monk provides Ashitaka with a shelter that night and Ashitaka opens up about his story.

The monk unearths his company’s identity, an Emishi, but promises to keep his secret safe. The monk guides him towards the forests in the West where giant Forest Gods dwelled, and it looks like the monk himself had plans to visit the place; the reason, however, remains unknown as of now. All of Ashitaka’s adventures and sights are complemented and elevated by the entrancing soundtracks by Joe Hisaishi.

The music helps deepen the association of the audience with Ashitaka’s circumstances and quests. In the next scene, he leaves the following day after paying his respects to the monk for his hospitality. The young man’s mind is filled with doubts, but there’s not an ounce of despair; his determination to find answers overpowers the gravity of his situation. It’s almost as if his strong will is bound to carve out a successful way for him.

Meanwhile, a large group of ox drivers and guards were carrying a contingent of rice up a hill. An enigmatic lady and her associate led these men, but soon, two oversized wolf pups attack the contingent, and one of them appears to be ridden by a human.

The guards use firepower to turn them away, but they keep coming back to attack. Soon, the mother of the pups and the Forest God of the wolves named Moro makes her presence known. The lady leading the men however turned out to be adept at using weaponry as she shot down Moro. Being a God, the giant wolf was not yet dead as that would be too quick and easy.

After Moro fell off the cliff, her cubs and the humans retreated in order to help Moro. A few of the men carrying the continent had also fallen into the river and in the valley below along with Moro. Ashitaka chances upon them and pulls out two of the men to safety. Suddenly Yaku is alerted by something; Ashitaka follows the sound to find Moro, her cubs and a beautiful young girl on the other side of the river. The girl was sucking poisoned blood out of the giant wolf’s wound. He introduces himself to the group, inquiring if he had reached the realm of the forest spirits, but all he received in response was an order to leave.

He returned to the fallen men and discovers a Kodama, a tree spirit. These little spirits make their cameo time and again in the film, right until the end. Fun Fact; according to Japanese mythology, the Kodama were spirits that looked no different than trees, but Miyazaki had designed them differently, possibly to make things easier for the audience. They were mute and mysterious creatures who liked to jiggle their heads making a rattling sound.

Ashitaka declares that the presence of Kodama was a sign that the forest is healthy. Naturally, he requests passage through the woods. Ashitaka and the men reach a pool surrounded by lush greenery and magical creatures. The Emishi saw what looked like the most elegant reindeer with an elaborate set of horns, but soon his cursed arm began throbbing with pain and shaking for reasons unknown. Submerging his arm into the pool his pain was eased, but the reindeer was now gone. They resume their journey and reach Lady Eboshi’s Iron Town.

The denizens of Iron Town were thrilled and stunned to see that humans made it out of the woods alive as no one had accomplished such a task before. Koruku, one of the men that Ashitaka saved, and his wife Toki are seen as comic reliefs in the film, to break free from the constantly tense atmosphere that engulfs most of the film. Although she’s overwhelmed to see her husband whom she presumed was dead, she is angry looking at his broken condition, clearly not fit to drive the oxen anymore.

Iron Town was nothing short of a fortress, but the men and women living there seemed happy and content. It was built on a destroyed forest, and its prime occupation seemed to be extracting iron from its ores. The ladies of Iron Town behaved flirtatiously in the presence of Ashitaka and it turns out that Lady Eboshi had employed ex-prostitutes to work for her. She bought these women and housed them in the Iron Town, giving them respectable jobs.

That doesn’t sound so bad, does it? Wait and watch as we find out that it was the same Lady Eboshi who shot the Boar God Nago with her rifle. The iron from the rifle had gotten stuck inside of him and he died; his body filled with agony and a heart full of hatred. These two sides of the Lady Eboshi that we see are contradictory; on the one hand, she was helping out prostitutes, and on the other, she was killing the forest gods.

But why did Eboshi attack the boar god? Well, after exploiting the plains and draining them of iron ore, the men wanted to clear out the forest on the mountain. This was unacceptable to Nago as it was the home of the bear clan. It led to a conflict that ended in Nago’s death, taking a massive toll on the proud boars as they resolved to kill Lady Eboshi and destroy Iron Town.

Lady Eboshi meets Ashitaka and shows him around, telling him how her town functioned, all her little secrets that even other townsfolk didn’t have a clue about. She shows him to her private garden and takes him to a hut where lepers were making the latest rifles. These rifles held enough power to kill gods and pierce samurai armors. Appalled by this, Ashitaka questions Lady Eboshi’s morals and ethics. She had shot a god, made his flesh rot, and corrupted his soul; he felt that she was the one responsible for his curse, and she still carried on making even deadlier weapons.

He was confused, trying to determine whether Lady Eboshi really was evil. She had not just rescued the prostitutes from their miserable lives but also rescued lepers, who were cast out by the society as it was believed that leprosy arose from sin. She had given their lives a new meaning and the will to survive, but here she was, attempting to kill the gods of the forests and tip the scale of balance. Why would she do that! Adding on to the villainy, Lady Eboshi also wished to kill the spirits of the forest that would take away the sensibility of the animals and turn them into regular beasts.

Killing the spirits would also make Princess Mononoke a regular girl. The little girl with the wolves was acknowledged just this once as Princess Mononoke whilst the wolves called her San. Interestingly, Mononoke in Japanese means an unknown or mysterious presence that can not be seen or sensed. It can be compared to the western urban legend of the Loch Ness Monster. Her name wasn’t intended to be Mononoke but just a description, similar to Batman being called The Silent Guardian and Watchful Protector.

However, her name gets lost in translation making the audience forever confused. Her real name is San, meaning three in Japanese. This is because the little girl was adopted by the wolf Moro, and was raised as her third child. This also bears stark similarity with Rudyard Kipling’s world-famous “Mowgli”.

Ashitaka intends to leave Iron Town to go looking for the forest spirit, but he stops as San reaches Iron Town to take Lady Eboshi’s life. However, the guards and the women of the town would do anything to save their mistress. They set up a plan to blow up the roof of the giant furnaces under which San would crumble and die. But Ashitaka decides to stop this. Although the Iron Town folks manage to injure San, Ashitaka rescues her displaying immense strength and mystical powers, and takes her to the forest and gets seriously injured in the process.

They escape riding Yaku, but Ashitaka slides and falls to the ground on the way. San’s wolf siblings wish to eat him, but she saves him. Was it partly because he called her pretty? (please show the scene) Even though San considered herself a wolf cub, she was merely adopted, and hence, her human instincts had never disappeared. So when a handsome young man complimented her looks, she was taken aback, quite literally.

By nightfall, there emerged a giant Daidarabotchi, or the forest spirit itself. In Japanese culture, the Daidarabotchi are giant entities that pose as mountains when they are asleep. However, Miyazaki took a different approach and depicted it as a giant astral figure. Wherever it stepped foot, the flora around bloomed and then withered, which made the Daidarabotchi the god of life and death. By sunrise, it had transformed into this deer-shaped forest god. Here we find the monk named Jigo’s true intentions with the spirit of the forest.

He wanted to cut off its head at the behest of the emperor, who believed that the forest spirit had the power of granting immortality. The spirit looked like a deer with a human face, complimented with a dense mane like that of a lion. The forest spirit was beautifully portrayed as the bridge between man and nature. It healed Ashitaka’s wound but strangely left his curse intact. Sometime later, San joined Ashitaka, who was still too weak to move or eat. In a romantic yet platonic gesture, San chews the food in her mouth and feeds it to Ashitaka.

In a strange turn of events, the boar tribe arrives at the forest to kill the humans but finds San and Ashitaka. After a heated verbal confrontation, the new leader of the boars named Okkoto joins in. He seemed to be the most reasonable of the boars but was blind. Okkoto believed Ashitaka’s story and his integrity but also threatened to kill them if he didn’t leave. Meanwhile, Lord Asano’s samurai thugs attacked Lady Eboshi and her men and the ensuing battle showed no clear winner.

Asano sends his men a peace message, but Lady Eboshi turns it down, awaiting its implications. Moro reveals to Ashitaka that San’s parents left her with Moro as a sacrifice to save themselves from her wrath. Naturally, this selfish act further tarnished the image of humans in the eyes of Moro. Lady Eboshi agrees to take all her men to Jigo’s cause even as the boar tribe approaches them for war. Meanwhile, Lord Asano’s men attack the Iron Town thinking that all the men were gone and the fortress was now unguarded. What they didn’t know was that Lady Eboshi had trained her women just as well.

In this three-fronted war with many motives, our male protagonist finds himself lost in the battle between his mind and heart. He loved San but couldn’t kill humans on one hand and admired Lady Eboshi for helping the helpless and downtrodden but didn’t want to be involved in the persecution of the beasts and San’s wolf family on the other. The curse was already tearing Ashitaka’s soul and flesh apart.

Nonetheless, he reached Iron Town in a bid to help the women. Ashitaka runs towards the forest to get Lady Eboshi back to her castle to lead the attack against Asano’s men, but he also intended on saving the spirit god. Three men chase Ashitaka on horses and injure his ride, Yaku. On reaching the battlefront somehow, he sees that all the boars had been slain in the bloody war. He convinced the Iron Town men to go back to town and save their homeland.

Ashitaka also finds one of San’s siblings and rescues him. He advances to save San and stop Lady Eboshi and Jigo from executing their plan. But, San was under Okkoto’s grip, who had turned into a demon himself and engulfed San, turning her as well. Ashitaka and the wolf cub hear their brother’s cries and figured that San was in danger. He rides the wolf bareback and finds Eboshi. The Lady tells him that she had trained the women adequately to fend for themselves and gets on with her plan to kill the forest spirit. Everyone gathers at the forest spirit’s pool, including Okkoto.

Moro who was already present was saving up her last breath to kill Eboshi, but changed her mind and saves her, by finding her daughter in danger. As the wolf god and the boar demon collide in an epic showdown, the forest spirit arrives, and both come to a halt. The spirit claims the lives of both the god and the demon, allowing them eternal peaceful rest. Ashitaka manages to save his love.

As the night progresses, another danger crops up as the forest spirit was now transforming into a Night Walker and was at its most vulnerable. Lady Eboshi shot a bullet into the forest spirit’s neck with her superior rifle and decapitated it. But the Night Walker transforms into a death walker with powers that could kill any soul it touched.

The beheaded Death Walker was searching the grounds for its head, growing larger in size, enough to engulf the entire forest and Iron Town. Meanwhile, Moro bit off Eboshi’s arm as revenge. Ashitaka somehow manages to convince San into helping a wounded Eboshi to get to Iron Town. The headless Night Walker begins unfurling death in every direction, not sparing trees, animals, and humans, alike. Ashitaka instructs the denizens of the Iron Town to seek shelter near the lake because the water would slow the monster down.

The young couple manages to stop Jigo from running with the head of the forest spirit and offers it back to the Night Walker. Sunlight falls upon the Night Walker just as he merged with his head and he disintegrated across the Iron Town; exploding into a giant gust of wind. Wherever this wind blew, it miraculously birthed a new plant and filled the area with lush greenery. It also lifted Ashitaka and San’s curse.

They realized that they couldn’t live together. The film ends on a very unconventional note as the two of them decide to meet whenever possible but never share life together. San paves her own way while Ashitaka joins Lady Eboshi in building a new town, albeit a more sustainable and environment-friendly one this time.

A pertinent question that the film poses is the blurred lines between good and evil. It is clear from the story that Eboshi was not entirely evil. All she did was for the betterment of her people, who saw her as their savior and held no qualms against her. In a way, she was their god. On the other hand, the audience is made to cheer for the forest gods at the beginning of the film, but as it progresses, we understand that they are not the epitome of goodness either. They have their own personal complications and even slaughter and curse humans.

As far as the forest spirit goes, we are of the opinion that it was neither evil nor good. It was just an entity that sought balance in the forest and went to great lengths to maintain this balance, often siding with different parties. Where Miyazaki stands in this struggle between the preservation of nature and the development of human life is a different debate altogether. However, one thing that’s clear is that both aspects are equally important.

As a film, Princess Mononoke transcends the boundaries of animated films and holds a meaning so deep and relevant that it renders several other Hollywood and international films hollow in comparison. Do let us know which films you think are a match for films akin to Princess Mononoke.