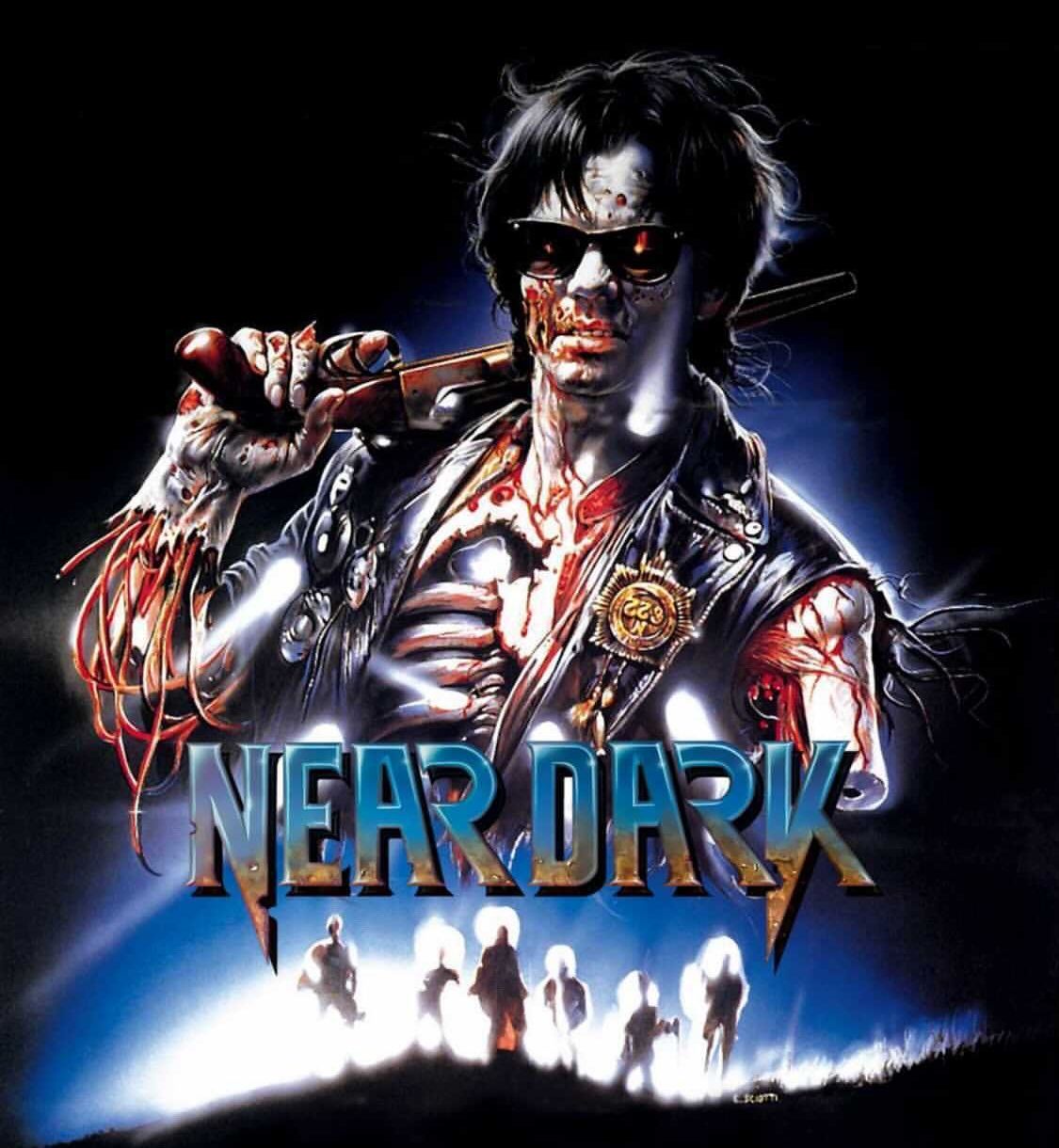

This video examines the film ‘Near Dark,’ which was one of the first major vampire films to forsake period dress and historical connections in favor of more grotesque elements. A poor mash-up of horror parody and genuine shock. Near Dark proves that horror does not have to stay in the B-movie closet to deliver chills and thrills. The film presents a terrifying Southwestern landscape packed with Peckinpah-style peckerwoods, unwitting victims, maniacs, and bloodsuckers: vampires twisted through a violent contemporary lens. However, an obsessive relationship lies at the heart of this tragedy. Every vampire picture has a sexual undertone to it, and the sensuality and heat in “Near Dark,” are particularly potent.

Near Dark is a romantic suspense story about a handsome young man who falls in love with a vampire girl and is lured into her nightmare realm. The plot was set on familiar territory, mostly from the 1970s and 1980s road movies, by Kathryn Bigelow and co-writer Eric Red. These are vampires from a postmodern society where faith has waned to the point where legends and faith are no longer effective. The film is full of well-drawn characters and moral complexity, as well as cultural observations that catch you off guard.

Near Dark never uses the word “vampire.” in his work. In a tough environment where pioneers and cowboys arrived, wiped out the indigenous people, and constructed their own romantic myth about their arrival not long ago, the film is set in a backwater town of shitkicker bars and pastoral farms. Nonetheless, in the Oklahoma setting, a car full of nightcrawlers began feasting on local blood. When exposed to sunlight, they soon become sunburned, but they are unaffected by garlic or crosses, and they have no desire to convert into flying animals. A cowboy, Caleb Colton (Adrian Pasdar), picks up the gorgeous Mae (Jenny Wright). He is transformed by her, who is a vampire. She and her tight-knit gang are on the loose throughout the United States.

On a night out with his pals, he notices Mae devouring an ice cream cone down the street. Colton, a loner, meets the fascinating Mae, whose familial relations are more fangy than friendly. Mae will soon agree to a night drive with Caleb, and his insistent requests for a kiss will result in a vampire bite. Even the children have fangs! When he is suddenly pulled off the road and into a speeding van, it appears that he is about to be a midnight snack for her family. Still, it is much more complicated than that, and this results in many chase sequences as he tries to get away from them even though Wright’s sharp-toothed kiss has undoubtedly impacted him.

Caleb’s truck won’t start, so he has to walk home. However, as he comes into contact with sunlight near his farm, he begins to burn. His father, Loy Colton, and his sister, Sarah, see a vehicle materialize out of nowhere and grab Caleb. He meets Mae’s family, including Jesse Hooker, his partner Diamondback, the ruthless Severen, and Homer. They all have one thing in common: they are all predatory night monsters that require blood to thrive. Caleb must decide whether or not to return to his cherished family. Caleb goes across a field on his way home, only to start smoking as the Sun rises. It’s no surprise Mae is captivated by the night sky: “It’s dark.

“It also blinds you,” she murmurs dreamily. Mae’s family, on the other hand, does not need more members, as they bring Caleb into their camper just feet away from his human family. Jesse gives Caleb a week to show his hunting and feeding abilities. If the terrified and ailing visitor succeeds, Mae offers him eternal life.

When a terrified Caleb attempts to flee the vampires and return to his own family—a motherless family with a veterinarian father and a little sister —he staggers into a bus station, ravenous and sweating, sprinkled in ash from his meeting with the Sun. Caleb’s unwillingness to kill causes him to shudder and exhibits withdrawal symptoms. Both the bus station clerk and a local officer believe he’s high. “What are you up to?” he inquires. Caleb ultimately re-runs into his family.

In the meantime, Caleb’s father has been looking for Jesse’s gang. Homer, a kid vampire in the team, encounters Caleb’s sister, Sarah, and wishes to make her his partner, but Caleb protests. While the gang is arguing, Caleb’s father enters and demands Sarah be freed at gunpoint. Jesse provokes him into shooting him, then regurgitates the bullet before wresting the pistol from his grasp. Sarah unlocks a door during the chaos, allowing sunlight in and pushing the vampires back. Caleb and his family flee the burning city.

Caleb advises that they attempt a blood transfusion on him. The transfusion suddenly reverses Caleb’s metamorphosis. After blood transfusions end up saving both Caleb and Mae from what Stoker refers to as “the curse of immortality,” in which they would spend “age after age adding extra victims and doubling the evils of the world,” Caleb gets the best of both worlds: an alternative life alongside Mae, albeit without the murderous necessity of vampirism. In other places, the curse is painfully portrayed through Homer; an old vampire stuck in the body of a young kid.

Homer, who exploits his youthful look to trap his victims in a horrible prank involving a phony bike accident, seeks to make Caleb’s young sister a buddy. While one might debate whether or not the blood transfer bit makes sense in the context of vampire mythology, one can equally argue whether or not they are, by definition, vampires.

Nonetheless, his looks make him weirdly sympathetic as he tears like a kid in dread of daylight and seeks solace in Diamondback’s arms. Caleb’s father and sister then pursue the savages until they face the realization that their recently converted family member may be a lost cause. It’s no surprise that Bigelow dressed the vampires in punk gear, leather, and torn jeans, to represent a familiar cultural identity that viewers in the 1980s would associate as a nonconforming type— both symbols of social decay and rebellion in the eyes of a conservative society.

Whatever compassion Bigelow has for the vampire family in the early part of Near Dark is dashed later, when they harass and slaughter the patrons and workers of a nearby dive bar. They intend to provoke Caleb into killing his first victim- to push him to do so. It’s the most promising part of the film since it illustrates the family. There will be action eventually. The vampires take over a sleazy pub, drink their fill from the deceased patrons, and deliver the film’s few purposely funny lines.

They engage in a shootout with the Kansas state police, which causes the most significant havoc by blasting holes in the walls of a bungalow and allowing sunlight to enter inside. Caleb is also reunited with his father and younger sister, who had followed him down. There’s a Hollywood happy ending after some last-minute plot twists. Jesse’s gang breaks into a pub and murders the patrons. They pour a pint glass with blood extracted from a waitress, Severen crushes a biker’s skull in his hands, and he cuts the bartender’s neck with his spur in the disturbing incident.

Mae exhibits her nasty side when she dances with a young guy who has just seen a killing and takes him as her sweetheart. However, Caleb continues to avoid murdering the easy prey, and the bar patron escapes—eventually, he informs the authorities of Jesse’s clan, resulting in a chain of events that leads to the family’s doom. When Jesse and his friends are finished at the pub, they set fire to it.

They leave the burning tavern and escape the scene. Caleb hits a patron in the bar scene, and sends him over the bar and against a wall, demonstrating his freedom to act on any violent desire and the strength that comes with that freedom. Caleb is surprised and delighted by his new skills in the brief scene. The film makes vampirism appealing due to Caleb’s power, the promise of immortality, and his passionate relationship with a creature of the night, Mae.

Caleb asks Jesse to inquire about their age, and Jesse responds that he “fought for the South,” which puts him around 150 years old. The idea behind putting the southern outlaw neo-western into a vampire horror context is that the already dangerous elements of scorching Sun and dry landscape become even more complicated: Bigelow’s use of this in the hotel firefight, for example, when an already unpleasant little gunfight is suddenly infused with the searing flesh and hellfire that comes with the aversion to sunshine, is just brilliant..

Add some romantic tangerine dream synth, an insane Bill Paxton in shades and a leather jacket, cutting necks with its fangs, and an overall smokey western hangout atmosphere that threatens to turn into a savage and hostile piece of gory neon horror. Caleb gets ‘cured’ of being a vampire after being rescued by his family and transfused with the assistance of his father. Caleb goes outdoors after supper, where he re-encounters Mae. Caleb refuses to re-join them when she asks him to because he belongs with his family.

Caleb walks upstairs to check on his sister Sarah when Mae flees, but she is gone. Caleb pursues the vampires after learning that they took her. Except for Mae, everyone wants to murder Caleb when he puts them at risk by allowing the last live inhabitant to go, but after Caleb puts himself in jeopardy to assist them in escaping their hotel room during the daytime, the police raid, Jesse and the others are thankful and momentarily placated. The vampires are looking for Caleb and Sarah.

While the others abduct Caleb’s sister, Mae distracts him by persuading him to return to her. Caleb finds the kidnappers and cuts his tires, but he pursues the suspects on horseback. Severen confronts him as the horse cowers and tosses him. More people are murdered as the struggle progresses, but the accurate measure of the fight’s condition is the holes ripped in the wall and the sunlight streaming through them, setting the vamps on fire as they try to duck into smaller and smaller areas.

Diamondback tries to murder Caleb with her knife by throwing it at him when he is attempting to find out where his sister is, by asking Jesse, but she misses and stabs Jesse in the mouth. Caleb tries to get back home after snatching his sister, but Sarah is abducted again, so Caleb follows them once more.

While the vampires try to flee Caleb, Mae grabs Sarah and climbs out of the car’s rear window, beginning to rush towards Caleb. But Homer, who desperately wants to feed on Sarah, leaps out of the car and pursues them down, but the Sun burns him to death. Homer’s death builds the solid foundations of the blood-sucking gang in ways they never expected.

The vampire genre is as ancient as the film itself, with many violent masterpieces to choose from. Bigelow and Eric Red’s script deconstructs the vampire concept while blending it with traditional Western tropes. Near Dark adds little to the vampire subgenre in terms of theme. It essentially concentrates on the idea of blood as a medicine.

The film is set in a backwater town of shitkicker bars and pastoral farms, in a harsh environment where pioneers and cowboys arrived, wiped off the indigenous people, and established their own romantic story about their arrival not long ago. Bigelow’s film never uses the name “vampire,” and its creatures, a nomadic family of assassins, lack fangs in favor of thirst for blood, fabulous fingernails, and immortality. Near Dark would become one of the first big vampire films to forego traditional clothes, historical connections, and some monstrous features.

The vampire is by far the most remarkable symbol in a horror film, and much of the enjoyment of “Near Dark” derives from the continuously shifting flow of meanings and associations Bigelow discovers inside it. Vampires assault urban areas, torch them, and leave dead in their wake. They lead nomadic lives, free of the rules of law and order imposed by white settlers, and are tuned in to a side of Nature that the civilized world cannot comprehend.

The distinction between vampires and humans is analogous to the difference between darkness and day. Caleb and Mae are most appealing to each other when these two poles change at Dark and dawn—the periods in the film when the lovers appear most reliant on one another. Mae asserts that now that Caleb is immortal, they may do “whatever we want till the end of eternity,” implying that their lives have no sense of finality or constraint.

The film’s biggest inventive leap links the European concept of the vampire to the American image of the Western outlaw, combining the underlying antisocial tendencies of the ancient and new civilizations. Vampirism, as a symbol of romance and erotica, indicates the interchange of essences between two people, offering a transcendence of death; it may also be a sign of nurturing tenderness, as Mae enables Caleb—who is still too afraid to make his kills—to feed on the blood from her wrist.

If Bigelow retains any part of Stoker’s original novel, it’s the guarantee of everlasting life that Dracula promises Mina, which Mae wishes to give Caleb. In both the book and Near Dark, there is an implicit attraction of escaping from the monotony of everyday existence into something odd and familiar, the promise of an alternative to normalcy through attaining eternal life. Near Dark might be understood as a reaffirmation of civilization.

This expression flirts with revolt only to restore order to the cosmos by placing vampires as wicked and alternative to ordinary forms of existence. The film makes vampirism appealing due to Caleb’s power, the promise of immortality, and his passionate relationship with a creature of the night, Mae. Bigelow puts issues in the viewer’s mind about where our allegiance should be directed, even as the film’s direction confirms conservative beliefs on unrealistic standards.

Consider how subsequent vampire romances, such as author Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight saga, embraced a progressive lifestyle, conjuring up a scenario in which humans and toned-down vampires might meet somewhere in the middle and live happily ever after. While Near Dark eventually adheres to traditional lives, it also examines and provides alternatives to the existing order.

“Near Dark,” an unusual and gory road movie and one of my favorite cult movies, is an earlier effort of Oscar-winner Kathryn Bigelow. The plot blends romance, crime, violence, thriller, and horror, which is a great film. Mae and her family are never referred to as “vampires,” although they are cruel and merciless to their many victims. Caleb is a young guy from a family who loves Mae and is forced to live with these wicked monsters.

There’s also dark humor in words. The film contains enough humor to make its gloomy vision acceptable, but there is also a guilty pleasure in its horror—as the characters live out our most fiercely suppressed urges. If there is a problem in the picture, it is in the closing act, when the required return to normalcy is played out too simply and quickly.

Near Dark, Kathryn Bigelow’s directorial debut, combines road movie, west, and horror elements, with the action occurring on the same long, grimy, uninhabited stretches of heated highway that formed screenwriter Eric Red’s previous effort The Hitcher such an impressively atmospheric film; this bleak location perfectly complements the harsh, emotionless, and seemingly endless existence of its antagonists, with the sense of desolation further enhanced by a brooding synthesizer.

Near Dark’s eerie and disturbing view of rural outsiders who are condemned to their way of life: hunting at night, hiding out of the light during the day is aided by the vampire aspect. Red’s script largely avoids the expected clichés: crosses, garlic, stakes, and holy water play no role, the killer lack fangs and many of the supernatural abilities usually associated with vampires, and it is even revealed near the end of the film that a blood transfusion can reverse their condition.

Near Dark does not look or feel like any other vampire flick. The closest visual parallel would-be Joel and Ethan Coen’s debut, Blood Simple (1985), which combines minimalist landscapes with a modern cowboy image into a neo-noir. Adam Greenberg, who shot The Terminator (1984) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, was the director of photography (1991). The deserted streets at night, newly hosed down by the workers and lighted by street lights, give Caleb and his new vampire family the impression that they are the only humans on the planet.

On the other hand, Greenberg shoots sequences during the day that are drenched with dust, resulting in beams of sunlight that make us hyper-aware of the material and, consequently, the threat it poses to the vampire family. Bigelow creates a calm, languorous cadence that appears seductive and tense. It gets close to the ambiance of Nicholas Ray’s classic film noir “They Live by Night,” thanks to the velvety night recorded by cinematographer Adam Greenberg.

Bigelow has no restriction in her visual and thematic symbolism, yet she does so with the agility that the ordinarily apparent imagery feels creative. Take, for example, the moment in which Caleb, who refuses to murder for a meal, drinks from the cut Mae makes on her wrist. Bigelow sets the feeding against an oil pump, suggesting the image of a human heart pumping blood while Caleb enthusiastically consumes. Bigelow and Red’s script contains multiple references to vampirism as a type of drug addiction in other sequences.

Near Dark is a fantastic horror film that is also incredibly depressing in several moments. The relationship between the two characters works, the villains of the plot, primarily Lance Henrikson and Bill Paxton, are terrifying and nasty, with a touch of lunacy that makes them unforgettable, and the violence is gory, visceral, and intense for what Bigelow is wanting. It’s a romantic, passionate, and terrible image of American nightlife that becomes both enticing and heartbreaking.

The tension between light and Dark in Near Dark persists since these symbols signify Bigelow’s modernist use of genres, her worries about traditional and alternative cultures, and her voice as an auteur. The film provides atypical alternatives at every turn, preferring to work in the delicate areas between daylight and sunshine. Consequently, in the picture, neither extreme feels totally at ease or harmless.