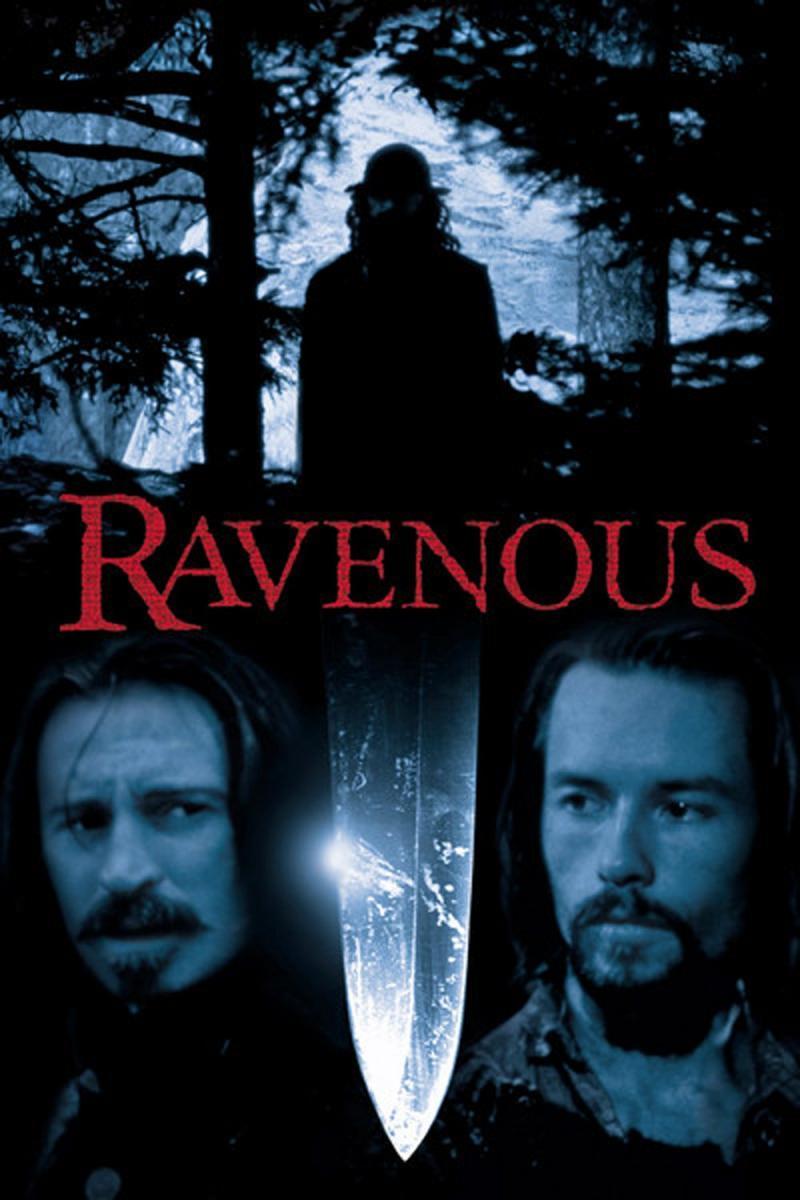

The film ‘Ravenous,’ which has been hidden behind the shadows of popular Hollywood sensations, is the subject of this video. Viewers and critics may not have been ready for a film’s viewpoint on certain issues and emotions, or the creators may have simply had bad luck dealing with fickle distributors and arbitrary release schedules, resulting in a product that was never seen. “Ravenous” is a suspenseful thriller about a flesh-eating sickness and the horrific power it possesses.

Thanks to strong performance and the incorporation of theatrical elements, the film does an excellent job of exposing its audience to horrifying possibilities. It is a gory horror film, a gloomy psychological drama, and one of Hollywood’s darkest black comedies. However, shrill does not always imply terrifying, rivers of blood and bleeding wounds do not always imply sensory pleasures, illogical leaps in logic detract from dramatic suspense, and dark comedies require more than a few poor jokes among bone-snapping carnage to inspire laughter.

Antonia Bird’s novel Ravenous skirts the line between horror and comedy. It has elements of both, but it never achieves the financial success that horror comedies have in recent years. Inspired by the literary works of Dashiell Hammett, Algernon Blackwood, and the real-life tragedy of the Donner Party, Ravenous’ tale is a harshly satirical meditation on the bounds of human civilization and the notion of manifest destiny.

Despite the lack of a traditional portrayal of the Native American monster on-screen, the film offers an incredibly human and atmospheric perspective on the Wendigo legend. Despite the fact that Ted Griffin penned this odd script, the final product appears to be very different from his original vision. The story periodically devolves into a muddle of tangled plot lines, but it ultimately works. This disturbance is primarily the product of some behind-the-scenes drama, which unwittingly provided us with such a unique film.

One of his most outstanding portrayals is Guy Pearce plays Second Lieutenant Boyd, a cowardly soldier from the Mexican-American conflict sent to a distant northern outpost in Ravenous. As he begins to mingle with the unusual garrison cooped up in the barren village, Boyd and the others learn about an ill-fated caravan that went lost in the woods and had to resort to cannibalism to live.

As the gang sets out to find survivors, they become entangled in a magical hunt involving the Native American legend of the Wendigo and an exceedingly suspicious Colonel Ives, played menacingly by Robert Carlyle.

The United States was a country of pioneers in 1847, with gold-starved Americans making their way to the west. It was a time of American Exceptionalism when the government felt compelled to stretch its borders, reach out its arms, and consume all the territory it could. During the Mexican–American War, Second Lieutenant John Boyd of the United States Army loses his bravery in combat and pretends to be dead while his battalion is butchered.

Along with the bodies of the other dead, his body is loaded into a wagon and taken behind Mexican lines. Throughout this phase of unrelenting consumption, Capt. John Boyd has become both a “hero” and a victim in ways he could not have ever anticipated. During the horrifying Mexican-American War fight, this act of stupidity results in his exile to a remote military outpost, a waystation for western travelers in California’s bleak and frigid Sierra Nevada mountains. Fort Spencer is a caretaking establishment in the middle of nowhere.

Boyd isn’t a solid guy, to begin with, blanching at the sight of a bloodied steak placed in front of him as his similarly starving companions bite in with relish. In Ravenous, he faces the horrors of war through a monster that Bird and screenwriter Ted Griffin depict with an exuberant sense of humor that only adds to the film’s bizarre terror.

Upon his arrival, he is met by a small, motley group of soldiers, including his commanding officer, Hart (Jeffrey Jones), a man who has pretty much given up on life; Toffler (Jeremy Davies), the fort’s personal messenger to the Lord; Knox (Stephen Spinella), the “doctor” who just never crossed a bottle of whiskey he didn’t enjoy; Reich (Neal McDonough), the fort’s chief of staff; no-nonsense soldier of the group.

Soon after Boyd joins the garrison, into this strange, chilly, and foreboding world staggers a frostbitten stranger called Colqhoun, recounting a harrowing story of how his wagon train became lost in the mountains because Colonel Ives promised the group a speedier path to the Pacific Ocean. Instead, he took them on a more tortuous route, trapping the group in snow for three months.

When they sought safety in a cave, they quickly ran out of food and were forced to devour one another. Col. Ives, his group’s military escort, deceived the company and, after getting stuck over the winter, rapidly turned to cannibalism. Ives grew fascinated with devouring human flesh, eating “vigorously” and without restraint—imbued with the evil spirit known as “Wendigo” by Native Americans.

They attempted to live by consuming their horses, leather, and even the dog. However, these efforts could not be sustained indefinitely. Colqhoun and his fellow travelers were driven to cannibalism due to famine, and he claims Ives resorted to murder. Colqhoun claims to have fled Ives’ homicidal need to satisfy his hunger, but others were left behind.

Beyond cannibalism and the drive to survive, Colqhoun’s story has far-reaching implications. It is based on an old Indian account known as Wendigo, which holds that a man who eats another’s flesh absorbs that person’s power, energy, and very existence. His hunger turns into an insatiable desire: the more he eats, the more he craves, and the stronger he gets.

There is never enough, and death is the only way out. Colqhoun is an intriguing, twitchy little creature who might have been played by Johnny Depp in the hands of a lesser filmmaker. Carlyle imbues him with a malignancy that taints his blatantly humorous touches, much like Bird and Griffin’s general approach to the subject. Yes, he’s not a completely serious bogeyman, but he’s more spooky than goofy.

Boyd and Reich investigate as the troops arrive at Ives’ cave. The army comes into the cave and witnesses the terrible cruelty wrought by Ives — glistening corpses hanging upside down with newly removed flesh – is about as gruesome as one could envision in a damned nightmare. Long before the whole narrative is revealed, the film has established its icy, menacing tone.

That occurs when the characters return to the cave, where the travelers are reported to have sought refuge. There’s a disturbing scene in which Reich and Toffler enter the tunnel and then journey into an inner cave, where they discover something unsettling. They find the bloodied remains of five skeletons and realize that Colqhoun is Ives, who murdered everyone, and all of Colqhoun’s acts are staged, and they are trapped.

Colqhoun’s new strategy is to murder and consume the troops. It’s too late; Colqhoun, who plays Ives (and is portrayed with maddening eyes by Carlyle), murders everyone but Boyd, who escapes by leaping off a cliff.

To really be fair, it’s easy to envision Bird relating with Boyd as he returns to Fort Spencer and is confronted with a monster set on consuming. Boyd discovers in the second part of the film that no one who met Colqhoun is still alive, and the surviving crew suspects him of murdering the others.

Meanwhile, a new senior officer has been sent to Fort Spencer: Colqhoun, now known as Col. Ives and dressed in command garb. Of course, no one believes Boyd’s account in the face of a respected colonel. Boyd must get vengeance on Ives for a cunningly cruel search-and-trap tactic that leaves Boyd’s squad ripped in gruesome rags. Boyd is again compelled to drink human flesh to restore strength and stop Colqhoun.

Most intriguing is Boyd’s moral quandary: he refuses to consume meat in order to become stronger, save to confront Ives, but he also refuses to allow Ives to cause any more devastation in the future. Fort Spencer is transformed into a cannibalism hotspot. The confusion about morality culminates in a gruesome fight which leaves you all wondering about the uncertain ending.

That confrontation is also the first of the film’s two key turning points, both of which involve the most memorable drawn-out sequences of violence. The blood pours freely, and there’s no lack of gored, dismembered bodies, yet these sequences are crucial in terms of Boyd’s development. Even when Boyd is secretly recovering from his gruesome wounds, we never witness the heinous acts of cannibalism that Colqhoun refers to.

The actual act of violence. For a film that isn’t reliant on current technology, virtually nothing about its visuals has aged, and the savage episodes of horrific murder are no exception. Boyd and the others quickly get acquainted with the Wendigo mythology after finding that Colqhoun is guarding an astounding secret, one that would eventually face Boyd with the ultimate carnivorous quandary: whether to eat dinner or be dinner!

There are several stories throughout history of individuals eating human flesh. Whether it’s stories of uncivilized islanders eating their own as a daily ritual, or levels of individuals being forced to eat others to survive, humanity has repeatedly demonstrated its willingness to consume its own.

Horror films have responded in kind. To be sure, movies tend to sensationalize cannibalism, but the excellent ones are powerful because the horror on the show is absolute. Cannibal movies have been highly beneficial to horror directors seeking to shock audiences. Of course, not every cannibal film is made for shock value by exploiting scumbags. Like many horror sub-genres, this sub-genre encompasses a wide range of films.

Some are purely for entertainment purposes, but others hold more profound implications to comprehend beyond wondering if you’d ever eaten someone under any circumstances. Sure, cannibalism makes us hungry, but it may also make us think. It’s not simple to state that death and cannibalism are handled with care.

The picture brilliantly teeters its contrasting emotions, as evidenced by Michael Nyman/Damon Albarn’s delightfully uncomfortable music. Bird and Griffin smartly follow horror legend Joe Lansdale’s method of encouraging the audience to laugh at what disturbs them since laughing just makes them more uneasy. Cross-cut views of McDonough’s pale, leering visage are all the more unsettling as he tries to strangle Boyd to death with a slapstick, Jacksonian final gasp of energy.

It’s fascinating how Ravenous moves among several genres while never totally succumbing to any of them—it’s a roller coaster trip in that way. Bird frequently created films that were difficult to define, such as her mental illness romance Mad Love (1995), which was recut into a bipolar-infused rom-com by the film’s producers. Ravenous includes sections that Bird desired to be eliminated, and she was dissatisfied with the final version; she wished to recut the film for European viewers one day.

Ravenous was released in 1999, although it had a problematic production that only settled down just before the film’s release, making it a marvel that such an unappreciated masterpiece exists at all. The project was supposed to be led by Macedonian filmmaker Milcho Manchevski, with an excellent original story written by Griffin.

Manchevski, on the other hand, departed the production three weeks into filming due to repeated rewrites, schedule conflicts, and studio meddling. Eventually, Robert Carlyle suggested that his close friend and partner Antonia Bird take over overproduction. She guided the crew to a fresh, darkly comedic vision that draws more inspiration from Looney Tunes than traditional period pieces and horror films. This paved the stage for a captivating movie that, although not always constant, is always engaging.

The film’s setup is more entertaining than its pay-off because we would rather dread what is about to happen than experience it in a plot like this. The film emphasizes the power obtained by consuming human flesh. A final conflict between two guys, both significantly reinforced by their peers, feels like one of those superhero clashes in a comic book, where neither side can lose. Ravenous seems as accurate as possible, not just because of the performances but also due to the visual portrayal of 1847.

Candlelight, flickering fireplaces, warm and cold exteriors, perilous mountain crags, and collapsing timberline all contribute to the creation of a really lived-in environment devoid of any phoniness. The cave-searching sequence, in particular, contains some of the oldest and most dissonant noises I’ve ever heard, which strangely contributes to the spiritual component of the wendigo subplot. Nature’s noises are twisted, warped, and produced into something entirely new and horrifying. It’s one of the most diverse horror soundtracks ever composed.

Ravenous, which was developed by Fox 2000, immediately became a problematic production for everyone involved, including original director Milcho Manchevski, executive producer Laura Ziskin, the cast and crew, and, eventually, replacement director Bird. Manchevski, whose Before the Rain won an Oscar and whose arrested development music video “Tennessee” received widespread acclaim at the time, was slated to begin filming on location in Mexico and Slovakia’s Tatra Mountains.

When the studio agreed to a compromise, Manchevski refused to sign off on the budget or meet with his production personnel to discuss their concerns. Worse, the studio deemed the first three weeks’ worth of video to be horrible; it wasn’t long before studio president Ziskin traveled to the location with a replacement director, sparking a strike among the cast and crew.

Despite the absence of a classic embodiment of the Native American monster onscreen, the film remains an extraordinarily human and atmospheric interpretation of the tale of the Wendigo. Though supernatural cannibalistic powers are clearly at work, the Wendigo is more of a metaphor than a flesh and blood ghoul in this story.

As a result, despite the fun, this winter thriller has some truly unpleasant concepts and visuals and would gratify any horror fan searching for depth with its visual feast. The fable of the Wendigo, has various versions, as do all mythologies. This film exemplified one. I watched it on the advice of a friend because historical films don’t generally appeal to me. This picture has an excellent storyline, actors, and cinematography.

There are certainly a lot of aspects that make the film as memorable today (if not more so) as it was in 1999, and they begin with the high-caliber performance and superb cast combination. Because the film is first and foremost a captivating plain drama, with the horrifying components naturally developing out of the theater, it’s no wonder that the quality of the writing drew this caliber of performing talent.

Carlyle was in the cast, and his fame had skyrocketed since Trainspotting and The Full Monty, making him a bankable celebrity. After working with Bird on Priest and Face, the actor recommended that she take over directorial duties (friends, eventually Bird and Carlyle would own the production company together, 4Way Pictures Ltd.).

A bird landed on the set at Barrandov Studios in Prague after ten days of talks with the company and found the inadequate facilities untenable. She described the working conditions as “terrible” and defended Manchievski, claiming he couldn’t be entirely responsible. You can’t talk about Ravenous without mentioning the shockingly strong performances from the whole ensemble, not just Pearce and Carlyle (though the interaction between these two is undoubtedly the heart of the film).

Both David Arquette and the late John Spencer have significant parts in the picture, and practically every minor character is at least fascinating, which is unusual in horror films in general. Despite its limitations, the screenplay does an excellent job of depicting these sad victims, demonstrating that there is more to them than meets the eye.

Nyman and Albarn combine goofy banjo tunes with massive instrumentals to keep up with the film’s drastically altering tone, substantially enhancing the experience. Ravenous’ music isn’t the only thing that stands out; Bird’s methodical pace and camera positioning provide an unexpected twist to what could have been an introductory slasher film. It employs non-period instruments throughout (flutes, mouth harps, accordions, strings galore, electronic sounds, and chanting).

And, although the composers have grim fun with the soundtrack and the cast playfully delivers their weird performances in various parts, Ravenous retains a sense of dread under the surface and works on multiple levels—as the finest horror comedies frequently do. However, as mentioned in this appraisal’s introduction, Ravenous does not lend itself well to genre categorization.

This strange blend of campy action and genuine suspense is what makes Ravenous such a unique experience. Still, it’s also what made the picture so unappealing to audiences in 1999, when it was both a critical and economic flop. Of course, a few commentators have declared that this is one of the finest undiscovered masterpieces of the 1990s throughout the years, but not many people have seen it since its first release.

The misconception that the United States is a feast with capacity for everybody at the plate is butchered by Ravenous, beginning with an American flag wafting in the breeze and ending with a column of new dead. This is a world where “manifest destiny” becomes a valuable euphemism for all kinds of evils, as well as a reminder that progress was never conceivable without violence; the frontier was, and always has been, the Hunger Games.

That may not be breaking news, but the film isn’t interested in telling you something you don’t already know, simply in showing you something so joyous and horrible that you’ll never forget it. As Bird embraced the dungy stench of B-movies to pierce the black core of the American Dream, both colonialism and capitalism are churned through the grindhouse. Despite its nihilism, this bizarre perspective on the strange, strange West goes so far into the darkness that it finally beams light through the other side.

A wacky mix of gory horror, adventure, western, humor, and satire! It’s challenging to accomplish, and most movies fail at it, but this one succeeds. The film constantly shifts gears on you, yet it always works. The plot takes surprising turns that you don’t see coming. The narrative contains several creative plot twists and turns.

The film goes swiftly, it’s brilliantly directed in some stunning settings, and it has a fantastic music score throughout. Ravenous is a historical comedy horror film set in the nineteenth century on the American frontier. It’s a world of extreme cold, snow, suffering, and cannibalism, as individuals stuck in isolated outposts are forced to feast on each other’s flesh to survive.

Suppose you can stomach this cruel yet humorous narrative of a primitive, dog-eat-dog America. In that case, you’ll be rewarded with a scary yet engaging treasure that proves it’s more necessary for a novel to be constantly intriguing than it is to be traditionally “excellent.” It may be problematic, but all of these features imply that Ravenous contains a bolt of creative lightning that will likely not be repeated, especially given the production’s murky narrative. This type of film makes you adore it despite its flaws.