This movie covers Amat Escalante’s film “The Untamed,” which is about the beast known as passion and how it can be alluring, all-consuming, and dangerous at the same time. As is customary for the bold Mexican filmmaker, that beast is depicted as a tentacled alien from space. The initial title was La Región Salvaje (The Untamed), which translates as “the wild region,” which could refer to anywhere in space, the dangerous beaches of human need, or this Mexican writer-uncontrolled director’s base imagination.

The strange premise of the picture is spelled out in the film’s perplexing opening sequence, which displays what looks to be a giant asteroid approaching the Earth. The asteroid has brought with it a new life form that the asteroid’s elderly discoverers — retired people living in a small cabin in the woods — feel compelled to keep concealed.

The plot of “The Untamed” is based on mankind and their need for pleasure, not necessarily from this monster. It is a low-key psychedelic sci-fi picture about a huge space squid making booty calls. It demands a “loud” and “silent” strategy. “The Untamed,” a psychosexual Spanish-language film by Amat Escalante, has been described in a variety of ways. “intoxicating,” “unforgettable,” and “wild.” are some of the adjectives used to describe poster art. Words like “entrancing,” “difficult,” “unusual,” and “unhinged.” are used by armchair critics.

Four people’s sexual lives and intimate relationships have been influenced by a strange tentacle thing. The Untamed is about what would happen if an organism could be kept in captivity that could provide exactly this kind of pleasure; an organism in touch with a fiercer, purer, more profound, and more simplistic sexual pleasure that our advanced life forms have only had a dissatisfying and vague hint of up until now.

Plot

A lot is going on in this movie. Escalante begins his narrative with incoherent imagery: a comet; a lady was eliciting self-pleasure (or not?), then she’s wounded rushes through the mist for her dirt bike. Then, as quickly as it began, the dream — comes to an end. We’re in vibrant and vivid Guanajuato, yet it’s filmed randomly. We come across a woman who resembles herself but appears more innocent.

Veronica is a young lady sexually attracted to a tentacled extraterrestrial species that originated from a fallen meteor and is kept in a barn in the countryside by an elderly couple. She’s been visiting the extraterrestrial for years, having sex sessions with the monster that make her swoon.

The beast bites her in the abdomen, despite never injuring her before. Fabian, a nurse looks after her at the local hospital, and she becomes friends with him. When she tells the elderly couple, that she wants to keep seeing the extraterrestrial, they warn her that she can’t sense it’s too hazardous for her.

The majority of the film is devoted to telenovela melodrama devoid of soap opera antics. Parents Alejandra and Angel enjoy breakfast with their two boys before dropping them off at school, then they go to their various occupations in a candy factory assembly line and in the field working construction.

Alejandra, a young mother of two, is dissatisfied with her marriage to Angel, who is having an affair with Alejandra’s brother, a nurse called Fabian. On the other hand, Angel makes fun of Fabian and gays in general in public. Alejandra is deeply dissatisfied sexually and carnal thoughts pre-occupy her.

Angel’s thoughts are soon discovered to be preoccupied with Alejandra’s attractive doctor brother Fabian (Eden Villavicencio). We see Angel and Fabian steal away from a raucous bar one night to make love, but we soon learn that they have two vastly distinct viewpoints on their wants and needs; Angel, a lower-middle-class construction worker, is completely closed off with his innermost desires, boiling up his acts of aggression into sexually abusive and violent text messages to Fabian.

The latter is a bit more honest even though terrible homophobia exists in their community. In an introductory scenario, spooning becomes something more yet remains elementary. She fantasizes and almost has an orgasm in the shower when her kids knock on the door and stop her. Angel is the epitome of toxic masculinity: harsh, aggressive, disrespectful, and uncaring lover, a disengaged parent, a guy who takes what he wants when he wants it.

He has a youthful and defenseless expression, and he’s a real jerk. Even though he has a severe allergy to chocolate and knows it would cause him considerable suffering, the couple’s younger son will not stop stealing nibbles from it.

That’s the dichotomy that sometimes runs through desire: we want pleasure now, even if it means suffering afterward. Even when we should know better, this dichotomy is also reflected in certain moments: half-dark, half-light — a gloomy chamber with the pair softly chatting, compared with a blazing TV screen in the corner.

Thanks to Veronica, Fabian’s new friend, the squid enters their life and develops her bond with Alejandra as the narrative progresses. It dwells within an empty room home amid the woods, under the supervision of an elderly married couple who realize both excellent and harmful potential.

It may produce ecstatic pleasure, as seen in the first scene with Veronica. But, like everything meaningful, love can harm its participants, as seen by the big wound Veronica has on her side, which she claims is the result of a rabid dog.

Fabian looks after her at the hospital, becoming friends with him. When she tells the elder couple she wants to keep seeing the extraterrestrial, they warn her she can’t since it’s too hazardous for her. Over time, Fabian and Vero get close and become great friends or even something more.

Angel pays a visit to Fabián and asks him furiously why has he not responded to his texts. Fabián notifies him that their romance has come to an end. Veronica persuades Fabián to go to the barn. Fabián is subsequently discovered nude in a field, sexually abused, and beaten into a coma.

When he is in the hospital, Alejandra finds his phone and reads the angry texts from Angel, in which Angel demands sex from him while threatening him harm. Angel is arrested at work, and Alejandra and one of Fabián’s co-workers who observed their disagreements testify against him.

“The Untamed” turns into a not-so-revelatory drama of sexual inhibition, with Angel succumbing to his community’s homophobia in a way that matches a couple of the film’s squid sections.

Eventually, it devolves into a family drama, with Angel transformed into a hammy monster who is mocked by townspeople and family members, and “The Untamed” hits its lowest, weakest sections when it should be building up to some can’t-look-away finale. There’s even a domestic quarrel between Angel and Alejandra once she discovers Angel and her brother’s secret, which Escalante presents with an uninteresting accompaniment of opera music.

Veronica comforts Alejandra, eventually convincing her to become the creature’s next consort. When Alejandra returns to Veronica, she inquires whether the beast who attacked her brother was the same one who attacked her.

Veronica lies, claiming that the creature can only give pleasure. Alejandra understands the truth only after another meeting with the beast. In a later talk with Veronica, the ladies speculate that the animal can erase anger and hatred. Mr. Vega, a scientist, and his wife Marta Vega and Marta explain the creature’s importance to Alejandra as Veronica watches her children.

Alejandra consumes psychoactive tea, engages in intercourse with the monster, and emerges as an emotionally transformed woman. Veronica takes Alejandra to the property, where the couple tells her about how the extraterrestrial came after something from the sky created a crater in a nearby field.

Animals of all kinds are copulating frantically in the cavity. The pair drug Alejandra and lead her into the barn, where the alien satisfies her. Vega and Marta, are responsible for finding young ladies to help this abhorrently strange creature’s desire. “It only offers pleasure and never hurts,” Veronica claims, but this is true only until it grows weary of playing with the same person. The ladies who have experienced it describe it as excellent, achieving a primordial and pure condition of the sexual act itself.

Angel has been released from jail thanks to Graciela and her husband. Angel and his family, however, are embarrassed when tabloids expose Angel’s gay liaison with his brother-in-law. Angel pursues Alejandra. Angel beats her when she refuses to reconcile. Angel takes out a gun but shoots himself in the thigh by accident. Alejandra assists Angel, but in a way that Angel did not anticipate.

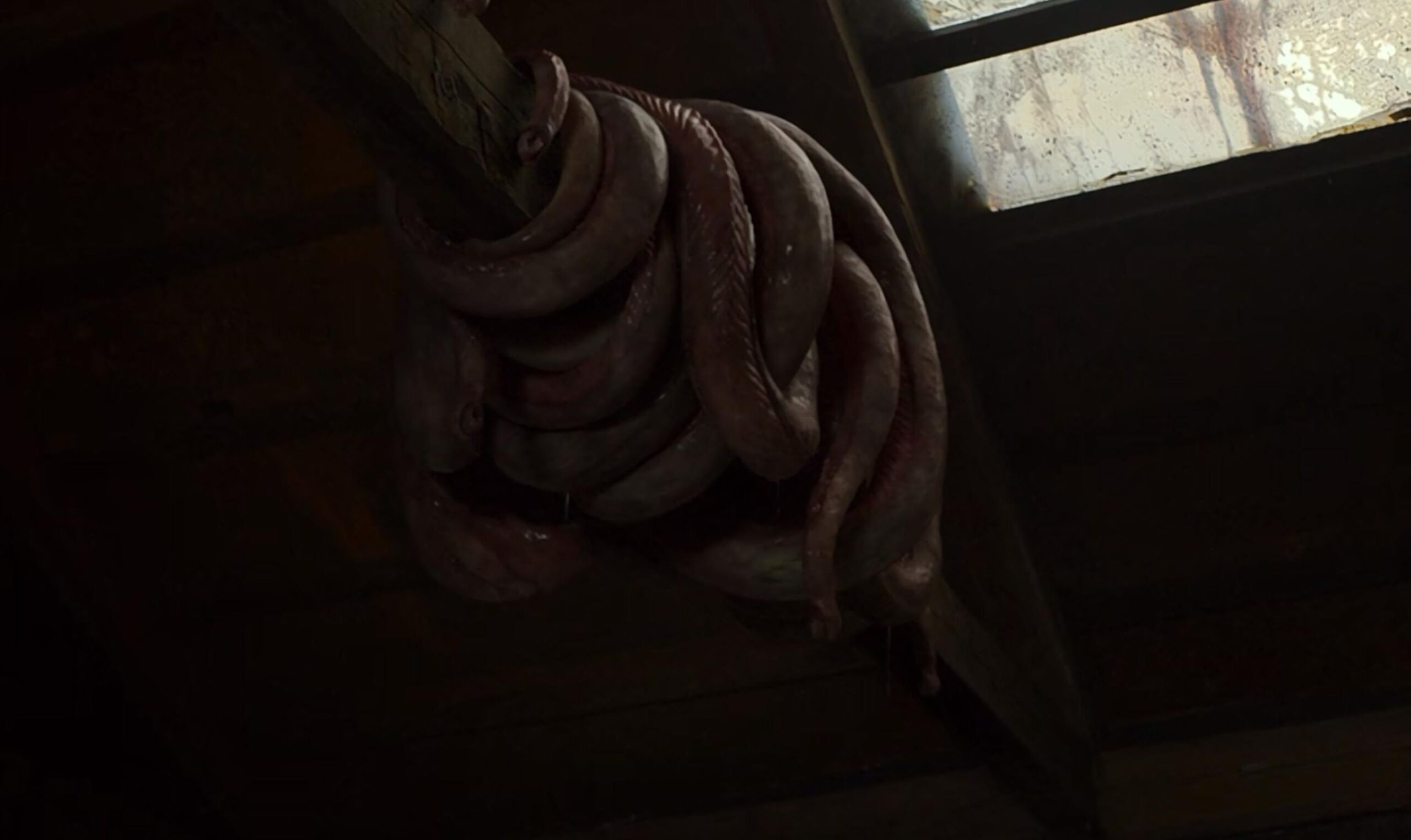

Ultimately, the creature devours those who were supposed to be spared by it. And what happens in the end? Unpredictable sequences. After all, the enraptures of the captivated is shown as though a serpent has coiled its prey in preparation for a large feast. “The Untamed” is an odd film.

It indeed does not resolve the concerns brought by the two storylines, but this pretty sleepy sci-fi drama remains an intriguing picture worth studying. The drama of Angel’s guilt of his affair with his brother-in-law, adultery, and his embarrassment at his gay impulses, as well as Alejandra’s guilt of her sexual pleasure from the randy creature, is an aspect that links to both story parts.

There appears to be a guilty-pleasure expression on the faces of those shafted by the slick tentacles, just as there is on Angel’s face when he Rodgers Fabian. The laughably abrupt finale leaves many of the story’s most pressing problems unaddressed, making The Untamed little more than a pompous art-house exercise in irritation.

The Lovecraftian monster

The monster aspect is early alluded to but takes its time to ultimately emerge, keeping things subtle enough for some low-key creepiness but not enough to whet the appetite of anyone anticipating a full-fledged creature film. The tentacular sex monster is a closely guarded secret. It is hidden away in a woodshed, and only a few are aware of its presence, at least in part because they are aware of its dangers: unconscious of its strength, it may murder humans who succumb to its penetrative caresses.

Its massive python tendrils creep into every pore, generating a memorable addiction that makes everything else the protagonists do in their lives appear dull and unreal. Escalante masterfully offers you only a brief peek at the start and then keeps it hidden from the camera until the very end.

As it consumes and is finally weary of its companions, the monster can impart either agony or pleasure to them. “The Untamed” has a nightmare, but it simply acts as a distant conceptual metaphor prompting arthouse drama to be ambiguously fascinating for those tuned to its dreamy personality study or painfully indecisive for anybody who seeks a firm foundation for fiction.

Review and Trivia

The story has a symbolic, even fabulous feel, but Escalante avoids oversimplifying his creature into a unipolar symbol. Instead, the picture addresses various social issues—homophobia, suppressed urges, sexism, addiction, and violence—without reducing the monster to a stand-in for any of them.

In Mexico, homosexuality is still regarded as an illness and a societal issue that must be addressed. The assumption is that LGBT people are essentially different from “we regular folks.” Common assumptions about Mexico’s macho culture may make us believe that the legal environment for LGBT rights in Mexico is significantly less equitable than in the United States.

In many cases, individual state actors have utilized state violence against sexual minorities with impunity. Men and women are not just dissimilar but also diametrically opposed. Boys who despise soccer, men who appreciate the opera or display unmanly emotions such as grief or tenderness, and spouses who help with housekeeping or care for their children are all deemed effeminate.

A woman who undertakes “man’s labor,” exhibits too much independence, or stands up to males is considered “poco hombre,” or excessively masculine. It’s simple to jump to the conclusion that she’s a man-hater and a lesbian. Homophobia is about more than simply homosexuality; it’s about what it means to be a man or a woman. In Mexican society, everything that deviates from established gender ideals is harshly punished; this is the underlying source of homophobia.

According to national statistics agency (INEGI) surveys, two-thirds of Mexican women have suffered some type of violence, with over 44 percent experiencing abuse from a spouse. In most situations, violence against women in their homes has remained beyond the mainstream concerns of the medical profession in Mexico, with only a few articles on the issue in the medical literature.

It takes time to change. Though Escalante and co-writer Gibran Portela set up this meeting of real-world prejudice and conflict with the other reality of unconstrained animal instinct, they don’t do much to progress either dimension or how they inform and affect one other.

Aside from the script’s magical trappings, the story of Alejandra’s home life is rich in dramatic depth and complexity: The image of her disastrous marriage to Angel, who forcefully exacts his self-loathing and self-repression on Fabian, is dense with subtext about Mexico’s glaring social and sexual inequities. Consequently, we get a very effective metaphor that should make arthouse entertainment value fans grateful for something as lavish and odd as it is intellectual.

The film is dedicated to Polish filmmaker Andrzej Zulawski, who inspired the notion with his cult film Possession (1981). Escalante’s picture owes a lot to Andrzej Zulawski’s 1981 masterwork Possession, which is also about a young lady fleeing an unpleasant marriage by copulating with a writhing mass.

Alejandra, who replaces Veronica as the alien’s lover when the latter is literally exhausted by its carnal power, does not exhibit the extreme deranged behavior of Isabelle Adjani in the Polish auteur’s film.

Still, she does undergo an awakening, transforming from a quiet victim of her society’s Catholic-influenced chauvinism to a liberated woman who stands up for herself, against her husband and her disapproving mother-in-law, and against popular morality.

The Untamed is not as wonderful as director Amat Escalante’s last film, the superb Heli (2013), about a high school student who accidentally is embroiled with a vicious drug-dealing gang. The cinematography in The Untamed is outstanding.

While the music sounds comparable to an Andrei Tarkovsky film’s ambient score, Escalante’s cinematographer, Chilean Manuel Alberto Claro, captures nature wonderfully and has previously filmed Lars Von Trier’s end-of-the-world thriller, Melancholia (2011).

“The Untamed” does not live up to classic sci-fi or horror expectations unless we’re talking about the horror of the human condition, where fragile balances between animal impulses and sentient aspirations hamper relationships with other members of our species. That is the actual adventurous voyage taken by “The Untamed.”

“The Untamed” has a monster, but it simply acts as a distant conceptual metaphor prompting arthouse drama to be ambiguously fascinating for those tuned to its dreamy personality study or painfully indecisive for anybody who seeks a firm foundation for fiction.

The setting of The Untamed is diametrically opposed to these stereotypes. Its depiction of small-town Mexico will be familiar to anybody who has lived in the countryside. In this place, boredom may lead to addiction, whether to drugs, alcohol, or sex with tentacled aliens. The film has terrific performances, breathtaking photography, and fantastic (but muted) music.

The filmmaker also did an excellent job framing each frame, and the film looks stunning. With voyeuristic closeness, an unrehearsed element in the tone conveys fragmented working-class life. “The Untamed” appears disconnected, a sequence of pretty pictures that make this a pointless form of mind scratcher.

Even with an outstanding aspect at the perimeter, everything reads as habitually mundane, stuck in the monotony that has as much opportunity of draining as it does of captivating a viewer’s attention, depending on personal ties to the talent underneath. Hollywood could probably learn something from filmmakers who choose aesthetics above finance.

Despite its unusual idea and the way, the film begins with foreboding emotions and crazy disconnected images right out of “Twin Peaks: The Return,” “The Untamed” delivers neither a crucial slow burn nor an atmosphere to be engulfed by.

The squid, with its enigmatic presence and all, becomes a simple, straightforward representation of people’s own quest for pleasure, particularly as a distraction from their own sadness. The film and its non-space characters fade throughout, as their feelings in this bizarre turn of events become minor.

It is difficult to compare this picture to any others that have come before it, which should only be seen as praise. We’ve got everything the carnage, sex, nudity, and monster feature excitement you’d expect from a genre picture.

It has the complexity and intrigue of an art picture, not to mention the cinematography, evoking the work of directors such as von Trier and Zulawski. At points, the film’s visceral, hate-filled violence echoes that of another Mexican film, Lex Ortega’s Atroz.

Minutes later, the sensual, inhibition-free sexuality on the show is evocative of Scott Schirmer’s underappreciated erotic fantasy/horror flick Harvest Lake. Of course, there’s the obvious parallel to Zulawski’s Possession. It would be conceivable to make a version of this film where the monster is never seen or does not exist: a performance in which the only thing that counts is the non-sci-fi realism love triangle of homophobia and loneliness.

These individuals have become accustomed to the constant nagging condition of discontent and longing that propels them ahead, like a donkey with a carrot dangling in front of it. For most individuals, that carrot is, of course, sex and love. Sex and love are thought to be the ultimate source of pleasure and fulfillment, yet their promise fades like a mirage.

Conclusion

The Untamed is one of the oddest movies you’ll watch this year. Escalante, famed for his gritty pictures of working-class Mexican life, travels into the magical realm. At the same time, the image maintains the social criticism and edginess that we’ve come to anticipate. This subtle, provocative, and scary dark tragicomedy is about a ubiquitous hidden addiction.

The Untamed is a fantastic blend of science fiction, horror, and sexuality. It’s enthralling, one-of-a-kind, and completely unpredictable. It delves into our fundamental cravings as well as our propensity for self-destruction.

The film’s vision is liberating. It not only challenges our perceptions of cinema genres and chauvinistic society, but it also plays with our perceptions of sound. In this regard, it evokes not just the auteur filmmakers already discussed here but also H.P. Lovecraft’s weird ethereal science fiction.

All of this may lead you to conclude that The Untamed is based on tribute, yet it refuses to be anything other than its own thing. As in Nicolas Winding Refn’s films, the acoustics heighten the suspense. There’s a lot of depth and enjoyment here. It creates a one-of-a-kind and pretty odd viewing experience.

It’s wonderfully off-kilter, with some stunning images. The Untamed is a one-of-a-kind picture that juggles genres in an unsettling manner. It’s a well-acted, well-written film that looks spectacular from start to finish. It is both sensual and terrifying, affecting the audience on both a visceral and cerebral level.

The Untamed will be either a terrible piece of a horror film or a celebration of the sexual pleasures shared by all beings, whether people, animals, or Alejandra’s beast, with benefits. Regardless of your experience with The Untamed, it’s a film you may find yourself wanting to return to.